John Archibald Marmaduke Friend. His name far more majestic than the 5 foot 6 inch, 130 pound man who almost filled size six work boots. Born in the Missouri Ozarks on a soft September evening in 1885, he took a bride shortly after century turn, and migrated to the red plains of Oklahoma.

When the Great Asiatic Flu Epidemic arrived in 1920 it carried away his wife and left him to raise six children, all under the age of ten, the two youngest under the age of four. No one knows how my sharecropping Grandpa could have plowed the fields for several years, while nourishing toddlers. He was eventually rescued when his widowed father came to live with him. And the two bachelor fathers would tend the borrowed land, and scrape out a living for a time.

He must have been enamored by the name "Myrtle", his first wife bearing the name, his second "Myrtle" arriving eight years later, two of her own children in her wake, widening the gyre of family to brood numbers. He loved both his Myrtles but his mistress would always be the land. Old John needed nothing more than a sharp plow blade and a good mule to produce sufficient bounty to keep his brood fed. He would walk through stately rows of corn and admire his harvest and he found nothing more beautiful than walking toward home at sunset, a waist high field of wheat caressing his belt buckle as he looked on the golden hue of his handiwork.

He was not a churchgoer. He was too quiet and unassuming to take to Southern Baptist tent revivals and all that shouting. His Myrtle had to be the disciplinarian of the children. He never raised his hand to a single one of them, but when he spoke, his words came so rarely they landed with more commanding impact. His only sin was the corn whiskey he kept buried beneath the smoke house, where the wild turkeys and hogs were smoked....hidden from a Baptist wife that would not have tolerated the consumption of demon rum and its distillations.

When the Great Depression arrived he managed to hunt for game, his wife husbanding chicken and hogs and a cow for milking. And his Myrtle canned fruits and vegetables that saw them through the long winters. And he kept growing corn and wheat and, an honest broker, turned over half his crop to the land's owner.

In winter, when there was no sugar, nor money to buy it, he would trod out to the snow blanketed fields, and gooble walnuts laying a foot below the snow. He would then walk into town and trade those walnuts for a pound of sugar. And when game was scarce the family ate squirrel and rabbit and, in the worst of times, the poorest offering of fried sparrow.

On April 14th, 1935, Black Sunday arrived with great fanfare to the Oklahoma plains. A dust storm five miles high roared across the land, leaving livestock dead, their stomachs bulging from the inhalation of two pounds of dust. Men too, caught out in the storm, would be found days later, having died from suffocation.

And on that April day, my Grandpa, turning 50 years old that year, must have surely despaired. Having courted his mistress for most of his life, she left him, her top soil blown away to distant realms. But, as tens of thousands of Okie migrants deserted that ancient red soil, bound for the fields and orchards and vineyards of California, my Grandpa could not leave his unfaithful mistress. He stayed, even as sisters and brothers departed in ancient Ford pickups, their mattresses and washtubs hanging perilously from the back pickup bed.

Grandpa stayed. And he moved on to find another sharecropper's field. And maybe the times shook him a bit. Perhaps he raised the gnarled old sharecropper's hands to his chest, and prayed for a merciful God sometimes. Or maybe, as he plowed the fields he sweet talked the wheat and corn stalks into bearing the fruit of their womb.

By the 1950's, when cancer and old age forced him out of the fields, he finally deigned to visit that California, where so many of his siblings and children resided. He came. He embraced his children and grandchildren, and not once did he reprimand them for their desertion. Not once did he say you traded the red clay of home for the cracked, alkaline cotton fields of Bakersfield, or the vineyards of the Central Valley. He simply came to see what all the fuss was about, then went home to die.

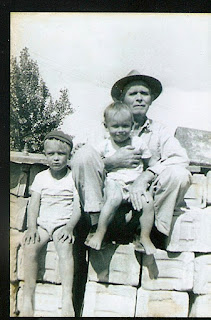

But one thing that never died. His legacy was one of great gentility, of honor, of pride, and his great love for his red clay mistress. And of the huge clan of Friends and Paynes you found not one who had a bad word to say about John Archibald Marmaduke Friend. Indeed, anyone who knew him could talk only of his being such a great man in a very small frame.

And if nature truly speaks, out there in those Oklahoma plains, there must still be the whispers of his mistress, longing for his loving and tender care.

2 comments:

Great read! Enjoyed every word.

Thanks so much, Carol. And thank you for giving me a few minutes of your life.

Post a Comment